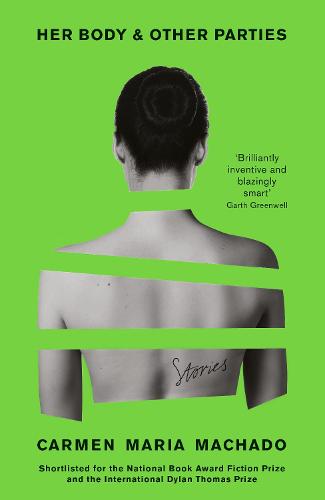

Carmen Maria

Machado’s Her Body & Other Parties (2017) is a delicious short story

collection which mashes up sci-fi and horror conceits with intersectional

feminist thought. Machado can WRITE, her particular

strengths being the depiction of appetites (for food or for sex) and the

creation of lush atmospheres. Machado uses fiction to explore female desire and

the plurality of womanhood, like imperial-phase Angela Carter refracted through

queer perspectives. Machado avoids a feeling I often have with short story collections

that the constant shifting of characters, premises and narrative forms stops

any single story making a deep impression: a couple of the characters and their

situations do stand out.

Among these is

the opening tale, ‘The Husband Stitch’. We follow a young woman who makes out

with a boy, marries him and has a child with him: so far so conventional. But

there is a difference. The woman has a green ribbon on her neck which is part

of her body; other women in this world seem to have similar ribbons in various

places. The man wants to touch and probe his wife’s ribbon because ‘a wife

should have no secrets from her husband’. Yet the protagonist says, ‘the ribbon

is not a secret; it’s just mine’. The man becomes more tantalised and more

pressing as the story develops, leading the woman to reflect: ‘He is not a bad

man at all. To describe him as evil or wicked or corrupted would do a deep

disservice to him. And yet –’. Men can be blatantly shitty, but they can also

be shitty in entitled, insidious and subtly forceful ways.

Machado suggests

that a long-lasting marriage does not mean complete knowledge of the other

person: private selves remain intact. The idea of ‘two becoming one’ is a myth

and sometimes a damaging one. This is not an entirely new concept; it is

treated for instance in James Joyce’s famous short story ‘The Dead’. But

Machado formulates a particularly male and particularly possessive desire to know. Knowledge, after all, is power. The

almost fairy-tale premise of the ribbons allows some female private self or

core of individuality to be physicalised and considered in new ways. Similarly,

in the world of ‘Real Women Have Bodies’ an affliction strikes only women where

their bodies, at different points in life but inescapably, fade away into translucency,

transparency and finally total incorporeality. These women then must go about

weaving themselves into the fabric of dresses in lament or disrupting voting

machines in protest.

‘Eight Bites’ is

a great story about what it’s like to live in a body that is all too corporeal.

It focusses on a woman whose sisters have all had a procedure that gives them

the perfect body so long as they apparently never eat more than miniscule

amounts ever again. She must decide whether to undergo the process herself whilst

navigating the disapproval of her daughter who is more traditionally feminist

and for whom body acceptance is the only acceptable way of thinking. At one

point the protagonist says:

‘I was tired of

looking into the mirror and grabbing the things that I hated and lifting them,

clawing deep, and then letting them drop and everything aching.’

I have not seen

this written enough. For many of us our bodies are a source of self-loathing.

Body positivity should absolutely be encouraged, but I don’t think it’s

un-feminist to want to change your body. It’s un-feminist to not understand why

women in particular might want that.

One slight flaw

in Machado’s collection for me is that some of the protagonists seem

undifferentiated: a chorus rather than solo voices that come together. The

worlds of the stories are differentiated but I can still always detect

the presence of an author with specific concerns who is perhaps trying to use

characters as vehicles for these concerns. That’s fine- Machado is an

entertaining and often pleasurable companion, whose interests overlap with my own. But Han Kang’s novel The Vegetarian (translated

from South Korean by Deborah Smith) achieves something that only a select few

of my favourite books do, where I struggle to imagine how anyone could possibly

have written it. It seems like something someone dug up or found lurking under

their bed, whilst focussing on similar themes to Machado’s collection: female

bodies, appetites and protests.

Kang’s novel may

be called The Vegetarian. But, Reader, the eponymous herbivore,

Yeong-hye, has not been inspired by Greta Thunberg or a lusciously voiced David

Attenborough documentary. No. Yeong-hye is a housewife in an affluent part of

Seoul, her husband noting her ‘passive personality’ and excellent cooking. One

day, however, she throws out all the meat in their house. She will go on to eat

less and less (for reasons I will not spoil). As she detaches herself from a

culture that gives prime place to meat-eating and her body begins to first slim

down and then waste away, her husband accuses her of being ‘self-centred’- of

acting ‘selfishly’ and with excessive ‘self-possession’. She is merely doing

what he has always done, but like the husband in Machado’s ‘The Husband Stitch’,

the husband here cannot accept that she has a private self inaccessible to him. Female independence is immediately

pathologized even before Yeong-hye’s weird dreams take deeper root in her

psyche:

‘Dark woods.

No people. The sharp-pointed leaves on the trees, my torn feet. This place,

almost remembered, but I’m lost now. Frightened. Cold.’

As in this

example, chilling impressionistic snapshots of Yeong-hye’s dreams are embedded

in indented type into the more ordered main narrative style. These moments are

the only direct access the reader receives to Yeong-hye’s psyche, and even they

are elliptical and fleeting. Elsewhere the novel’s tripartite structure offers

us views of Yeong-hye from the outside- the perspectives of her aggressively average and self-absorbed husband, of her

brother-in-law who definitely isn’t just a creepy perv because artists are

special, right?

Lastly we get her

sister’s take, for whom Yeong-hye is a figure of equal parts terror, bemusement

and inspiration. Yeong-hye’s sole focus on her relationship with herself and

her body reveals the fact that In-hye’s identities are primarily relational-

she thinks ‘as a daughter, as an older sister, as a wife and as a mother’ and

‘her life had never belonged to her’. Her sister’s ‘magnificent

irresponsibility’ provokes admiration and disapproval in equal measure, and the complex development of their

sororal bond is at the heart of the narrative’s ending.

As with Machado’s collection Her Body &

Other Parties, the power of Kang’s narrative is that there is no direct,

on-the-nose allegory- you cannot uncontestably state that in ‘The Husband

Stitch’ ‘the ribbon is her private identity’, or that in The Vegetarian ‘Yeong-hye’s

vegetarianism is a feminist protest’. Though they do seem to contain these

meanings, leaving things implied allows for a symbolic resonance murky and

powerful. What is clear is that female bodies, with all their protuberances or

diminishments, sticking out or wasting away, are the centre of desire, shame

and even protest; sci-fi and horror conventions are a potent prism through

which to write these experiences.

No comments:

Post a Comment